Few things provide a more pristine snapshot of a particular decade or era than its ephemera. Flip through an old magazine from the 1950s, and what is the most simultaneously fascinating and amusing part of it? The advertisements—irresistibly retro and unintentionally funny, reflective of long-gone mindsets and very different times from our own. (You get the same effect from ancient TV commercials or those hilarious, admonishing filmstrips they used to show kids in school.) Another category of ephemeral material stirs up similar feelings of bemused wonderment; witness these public-service pamphlets that evoke a troubled and challenging chapter in the saga of the U.S. Navy—the late 1960s and early ’70s.

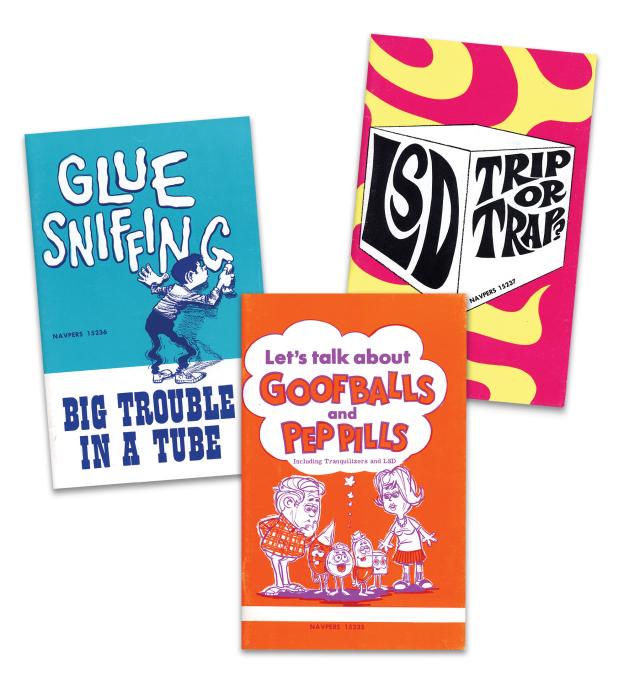

The service at that time was, in a sense, a collateral victim of the Zeitgeist: the explosion of the ’60s drug culture, the unrest on the home front amid a protracted overseas conflict, rising levels of angst and cynicism, and a nagging sense that the nation was standing on quicksand. For the Navy, it was a rough stretch as it tried to stay the course through all the societal madness. And a change to Article 270, U.S. Navy Regulations, cracking down further on the possession of narcotics as their use became more widespread, prompted the Bureau of Naval Personnel to publish these colorful pamphlets in the late ’60s.

Now housed in the U.S. Naval Institute Archives, these little publications obviously address very serious concerns. Yet in every aspect—from the wild lettering to the nutty cartoons to the garish colors—they also serve as pure 100-percent time-capsule material. They vividly capture their specific psychedelic moment in time. And in their attempt (one guesses) to be “with it” and therefore relevant to their target audience, they also have the unintended side effect of coming off a little bit moonbat crazy—albeit in a groovy kind of way.

Thankfully, of course, the Navy weathered the 1960s–70s storm and emerged from it stronger and more capable of dealing with such issues. But these relics of those difficult days serve to remind us of how even the most throwaway-seeming object can become a treasured cultural artifact—a window into yesteryear.

—Eric Mills